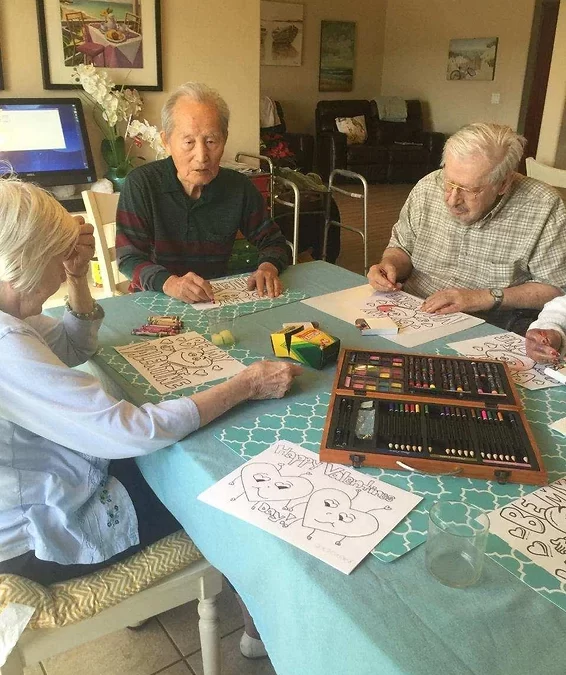

Activities at Lily’s Promise

Our residents have been clowning around this month with Starburst the clown, bird watching in the sunshine, and being crafty making Valentine artwork.

The lump-in-the-throat poignancy of working with seniors who suffer from dementia or Alzheimer’s disease has been front and center in Patrick Bismuth’s business life since 2009.

It ranges from conversations with a 90-year-old woman about long-ago deceased love ones to buying sweatpants with a drawstring for an elderly man who struggles with incontinence.

In this work, Bismuth, a onetime IT consultant who ran his own business working with Fortune 500 companies worldwide, sees a significant business opportunity. It comes through Lily’s Promise, a residential senior care company. One five-bedroom house in Sarasota, east of Interstate 75 near Laurel Oak Country Club, opened last year. Another house in east Manatee County, in GreyHawk Landing near Lakewood Ranch, is scheduled to open later this spring. If the first two homes prove successful, Bismuth, 50, hopes to open three new homes a year in the region going forward.

Bismuth has already invested nearly $1 million of his personal savings in Lily’s Promise, mostly to buy the homes. In addition to the investment, Bismuth has also regularly confronted his biggest obstacle: industry understanding and acceptance. Florida laws, through the Department of Elder Affairs and the Agency for Health Care Administration, oversee family care homes in private residences. The homes are maxed out at six residents per house, but otherwise follow rules for bigger competitors.

Yet the idea of a home for seniors smack in the middle of a residential neighborhood can be jarring to residents, and can also project what Bismuth calls a false sense of un-sophistication. “There is a stigma attached with small homes that make it hard to market directly to the consumer,” Bismuth says. “They envision small homes being less professional.”

Lily’s Promise is a counterintuitive venture in multiple other ways.

Part of the model, for instance, to pay higher wages with a smaller patient-to-caregiver ratio, runs counter to the pack-‘em-in model prevalent in senior care. Lily’s Promise also makes a point to seek out patients with a higher medical acuity, people who can be more difficult to work with. Because of the high-end model and tougher patients, Lily’s Promise only accepts private pay residents, with no Medicare or other programs.

“We want to take the residents who fall through the cracks of assisted-living facilities,” says Bismuth. “It’s smart business, but it’s also necessary for society.”

Open space Another differentiating factor in Lily’s Promise is going small at all. A current senior living industry trend, particularly in memory care, is to build a series of complexes that make up a neighborhood. That replaces the old way, of building large towers that house residents in dorm-style quarters.

Either way can be costly: Construction of a senior living home runs up to $250 a square foot. Bismuth says his housing costs are considerably lower, around $120 to $130 a square foot.

But Bismuth will spend more on labor. The industry average is around 33% of revenues go toward payroll. At Lily’s Promise, says Bismuth, his labor costs are closer to 60% of revenues. The company has seven caregivers, mostly certified nursing assistants, and four managers. Bismuth, in an effort to attract top CNAs, upped the standard starting wage, from around $9.75 an hour to $10.50 an hour. He also offers caregivers a 10% bonus for meeting work attendance and care goals.

Bismuth paid $350,000 for the 2,400-square-foot house in Sarasota and $450,000 for the 3,000-square-foot house in Manatee County. He’s spent at least $100,000 more on renovations and upgrades.

The floor plan of a home is a big part of what drives the home-buying decision for the company, says Kim Brownstein, head of business development for Lily’s Promise. Open space is essential for both residents and caregivers. “It’s nice to be able to see everything at once,” says Brownstein.

The Greyhawk Landing home, with residents expected to move in by May, is a standing example of the high-end approach Bismuth covets. The décor is Florida Keys style, with neutral colors and soft tones. The kitchen is open, with space for multiple employees to prepare meals. “The residents are spending a lot of time indoors,” Bismuth says. “So why not make it as luxurious as possible?”

Other parts of the home have been modified, to meet with industry safety codes, senior living facility regulations and common sense when working with a memory loss population. “Even though we are a small footprint, we have the same rules,” Bismuth says.

Doorways, for example, were enlarged to make room for wheelchairs. The home also has a high-tech alarm system, with a voice-activated announcement when an unauthorized door opens. The bolt on the front door is commercial grade. The expense is a business necessity, say Lily’s Promise executives, in a niche of senior living where residents walking out unwittingly is a major worry. “We go above and beyond to make sure our residents our safe,” says Bismuth.

Turn around Bismuth’s strategy with Lily’s Promise comes mostly from two areas: his entrepreneurial background and life lessons learned his mom.

The entrepreneur side started back in his native Montreal, when a 7-year-old Bismuth went door-to-door selling boxed cereal his dad bought in bulk. He later moved to California, where he earned an M.B.A. from UCLA’s Andersen Business School. By the time he was 28 he was running his own IT consulting business, traveling worldwide for clients. In 2000, then living in Ohio, Bismuth got into real estate and built a company that bought and rehabbed apartment complexes.

It was through that work that in 2008 Bismuth took over operations of a struggling 200-unit retirement community in Columbus. He helped turn the complex around, and in doing so found a new life passion: working with elderly. He had relatives in the Sarasota area, and, with the obvious demographic lure of the region to his industry, he decided to open Lily’s Promise.

His passion, he says, also comes from his mom, Liliane Sarfati, who Bismuth says was “always more concerned for those in her care than herself.” Sarfati, who didn’t suffer from Alzheimer’s or dementia, died in 2012. Lily’s Promise is named after her.

“Push Forward” Bismuth says out of multiple startup challenges, one is something many new businesses in a crowded marketplace face: proof the model works. “We have an idea of a concept,” says Bismuth. “We don’t know how we fit in.”

Brownstein, who worked in memory care and senior living in Ohio and relocated to Florida for Lily’s Promise, visits other area senior living facilities to introduce the business. Through those relationships and other marketing efforts, Brownstein and Bismuth aim to get in front of their target audience — adults in their mid-40s through mid-60s. Those are people who might have parents at a stage in life that makes them a fit for Lily’s Promise.

Another challenge, past marketing, is to create systems and processes that will save time and costs when the business expands beyond two homes. Bismuth has already begun to address that, from payroll software to grocery deliveries. Bismuth believes there’s a way to maintain the personal touch Lily’s Promise strives for without neglecting the systems that make a bigger operation successful. “You have to duplicate your systems well,” he says, “otherwise you waste too much time.”

Bismuth, so far, is both the numbers guy and the one who helps out with operations, branding, hiring and everything else, down to fetching Amazon packages and mail. His mom’s legacy and his business spirit motivate him to push forward on Lily’s Promise. “We’re excited about making a difference,” he says. “We are excited about helping people who have no other place to go.”

This story was updated to reflect the correct spelling of Liliane Sarfati and the maximum amount of residents allowed in a home-based nursing home.

– See more at: http://www.businessobserverfl.com/section/detail/the-promise/#sthash.z1QVnzU8.dpuf

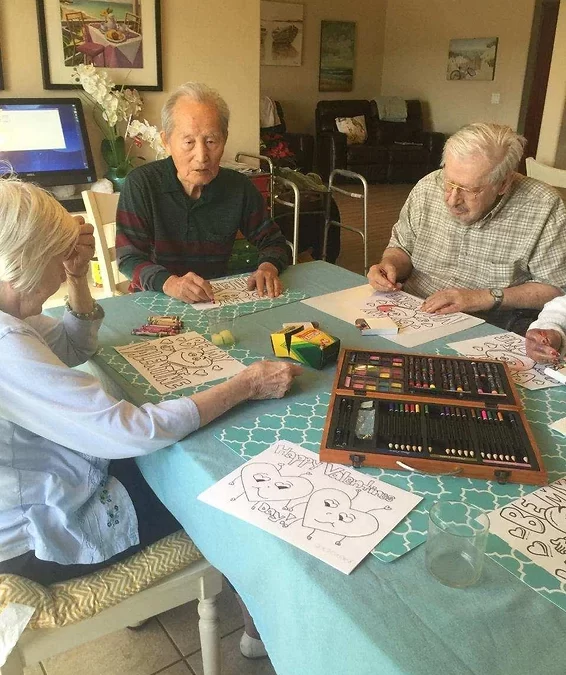

Ed Greelegs and his wife, Susan Holik, at the Lily’s Promise residence in Sarasota. Greelegs received a diagnosis of early-onset Parkinson’s disease at 50. Now 65, he gets personalized care at this six-person home.

Tall, soft-spoken and dignified, retired from his pivotal career on Capitol Hill in Washington, Ed Greelegs spends his days in a comfortable home in an east Sarasota neighborhood.

He watches TV with his housemates, shares meals with them, takes the air in the back yard, and comes alive when anyone strikes up a conversation about politics.

Because of his Parkinson’s disease, some days are better than others. The progressive neurological disorder that has made walking a struggle and most memories irretrievable is also fickle in the severity of its many other symptoms. His medications must be administered carefully, on a consistent schedule.

Another notorious quality of Parkinson’s — making it difficult to diagnose and treat — is that no two cases are exactly alike. Some people develop its characteristic gait problems and fluttering hands right away, and others never do.

But few Parkinson’s patients have experienced as many twists, turns and challenges as Greelegs, 65, a former longtime chief of staff for Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois.

He received his diagnosis early, at the age of 50. After two near-fatal medical emergencies in Bethesda, Maryland, his wife, Susan Holik, had him transferred to Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, where they heard about a place in Florida that offered an unusual array of resources for people with Parkinson’s: Sarasota.

In two and a half years here, as his symptoms progressed, the devastating setbacks continued. But now Holik believes she has found a safe haven for her husband where he gets careful attention from people who have come to know him. It’s a six-person residence operated by a small company called Lily’s Promise, using a model new to this area, and offering the kind of highly personal approach that a larger facility often cannot.

An estimated 1 million Americans have Parkinson’s, with about 60,000 new diagnoses each year. About 4 percent of those, like Greelegs’, are the early-onset variety. Researchers do not know what causes Parkinson’s, or why it afflicts more men than women. The disorder worsens as a dying-off of neurons in the brain causes it to stop producing dopamine, the “feel-good” chemical that regulates movement as well as emotions.

“The thing that most people don’t get about Parkinson’s,” Holik observes, “is that it’s not just a motion disease, that there’s so much more to it: all these cognitive, emotional, behavioral and other issues that you don’t really understand unless you make a study of it, or live with someone who has Parkinson’s.”

Sunshine and a social life

Because most cases of Parkinson’s are diagnosed after the 60th birthday, it makes sense that a region with more than 40 percent of its population in that age group would see a higher incidence of the disorder.

So far, the latest available county-level statistics on Parkinson’s, from 2010, show no cluster in Southwest Florida that would exceed its demographic profile.

But those who work closely with families affected by the disorder say they know of people with Parkinson’s who came here specifically for the combination of warm weather and local support.

Neuro Challenge Foundation, a free patient education and guidance service founded in 2008, hosts an annual medical symposium on Parkinson’s disease that draws a national audience, and is serving some 1,400 clients, says just-retired executive director Judith Bell.

“One or two people told us that they came to the symposium, went back and sold their home and moved to Sarasota,” Bell says. “We also are hearing from adult children who are living here, who are encouraging their people to move down because of the Parkinson’s services.”

When Parkinson Place, a drop-in center with daily classes and activities, opened more than three years ago, some in the local Parkinson’s community wondered if there was room for two nonprofits competing for the same clients and donors. But the organizations appear to co-exist peacefully, referring patients to each other and creating a kind of network of services. Executive director Marilyn Tait says Parkinson Place has hosted about 750 people.

“They come to Sarasota, and they say they want to come to our center because it’s their home away from home,” Tait says. “I tell them that if you have to have Parkinson’s disease, you’re in the right city. We have the finest resources anywhere.”

Lynn and Brad Schramek moved to Sarasota in 2012, when the harsh northern winters made getting around difficult for him. She brought with her the Parkinson Cafe, a cultural and social activity group that she founded in upstate New York.

“My husband Brad was diagnosed in 2005 when he was 45,” she says. “We found the right medical treatment, became involved, and by 2009 I was looking for a new program and I couldn’t find one. Brad had been a Type A corporate executive; we had to recreate our lives and fill our days with things that we can do that we enjoy.”

Researchers have noted that the Parkinson’s population includes a disproportionate number of knowledge workers — executives, engineers, doctors, accountants and even journalists. Coincidentally, this description also applies to Sarasota’s retirement demographics. One theory is that people in more physically demanding jobs get more daily exercise, which can slow the development of Parkinson’s; another is that more-educated workers live longer, and chronic disease risks climb with age. But it could also be that people who fit this profile are just more likely to seek and obtain a diagnosis.

A terrible thing

Susan Holik says their journey started when she noticed her husband’s finger twitch, and immediately blurted, “I think you have Parkinson’s!”

“He said, ‘That’s a terrible thing to say,’” she recalls.

After his diagnosis, which for Parkinson’s consists of ruling out other possibilities, Greelegs continued working for a while. At his retirement in January 2007, Durbin honored him with a speech on the Senate floor, calling him “one of the most well liked, even beloved figures on Capitol Hill. … He knows everybody and everybody knows him.”

About six years ago, Greelegs developed a urinary tract infection and ended up in a Bethesda emergency room.

“When you have Parkinson’s and you get a UTI,” Holik explains, “your behavior changes and you look like you’ve lost your mind. They didn’t know what it was, and thought maybe he was having a psychotic episode. They intubated him” — inserted a breathing tube — “and gave him massive doses of Propofol,” a general anesthetic. “He went into a coma. They said he would never emerge from the coma.”

After about nine days, Holik says, she agreed to withdraw her husband’s life support. Friends came to say their goodbyes. And as the powerful drugs left his system, Ed Greelegs woke up.

After a second incident at the same hospital, where a dose of morphine brought on another coma, Holik transferred him to Johns Hopkins, where he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s-related dementia. Physical recovery took a year. When a fall put him back into rehab, she gave up her career as a litigator to move to Florida. By that time, she had become an expert on Parkinson’s.

“I’m someone, if you give me a project, I’ll just look straight ahead and get it all done,” she says. “The winters are really hard if you have Parkinson’s, especially with slipping on the ice. We needed to get into a warmer climate.”

Once in Sarasota, the couple took advantage of all the Parkinson’s programs, as well as political and cultural pursuits. Then in May 2015, Greelegs fell while walking on St. Armands Circle, puncturing his liver. He needed surgery, and more anesthesia, which, Holik says, accelerated his dementia. After trying to care for him at their condo, she finally decided to place him in an assisted-living facility.

Then the facility informed her that he was falling too often, and had to go.

“I think I looked at every place in Sarasota for memory care when I was told I had 45 days,” she says. “A lot of people blackballed him, essentially, because he was already listed as a fall risk.”

Different every day

Patrick Bismuth and Kim Brownstein met when they worked together at a large retirement home in Columbus, Ohio. They modeled their new Florida venture after an Ohio business that operates a chain of nine small care homes — private residences, but with a 24-hour, certified staff instead of live-in owners. They have one house in east Sarasota, where Greelegs lives, and are in the hiring process for a second one in Manatee County, near Lakewood Ranch.

Lily’s Promise is a licensed assisted-living facility, but on a very small scale. The staffing level exceeds what is required by the state, Brownstein says, so there is no extra charge for the added care needed as dementia progresses. The cost, she says, is comparable to that of memory care at a larger ALF. The difference is that the residents and caregivers see each other daily, in a homelike environment.

“I named the business after my mom, Liliane,” says Bismuth, the owner. “I wanted to follow a corporate culture where you almost put yourself second to everybody else you’re caring for, which my mom did every day of her life.”

Bismuth and Brownstein, who handles the firm’s marketing, hope to open two or three new homes a year, in response to what they see as a pressing need for personalized memory care. Every resident in Rolling Green, the Sarasota home, was asked to leave a larger facility that could not provide the extra attention they require. Greelegs is their first resident with Parkinson’s.

“It’s something we wanted to do when we started,” Brownstein says, “but we didn’t have Parkinson’s patients knocking on our door. With Parkinson’s, that patient looks different every day. In a larger ALF, they can’t adjust that level of care. Here, you get to actually know each resident. If someone’s acting a little funny today, you’re going to notice and tell someone.”

In larger facilities, Bismuth and Brownstein believe, most falls and toilet accidents happen because no one is available to help residents to the bathroom. At the Rolling Green home, staffers can monitor every room on a screen in the kitchen and on their iPads. A security system announces, gently, the opening of every door. Although the bedrooms are private, Bismuth says, residents spend 70 to 80 percent of their daytime hours in the common areas, watching TV or gathered at the large kitchen table.

“When folks move here they usually gain weight,” Brownstein says, “because of the scratch cooking, but also they’re sitting around a table and the staff members are there to engage with them and do lots of prompting.”

A really urgent need

Andrea Gilmore-Bykovskyi, a School of Nursing fellow at the University of Wisconsin who has published research about the effect of person-centered care on the behavior of nursing home residents with dementia, says the value of such an approach is difficult to measure scientifically. But there is evidence that direct caregivers recognize changes in behavior a full day before nurses do. In larger institutions, she says, these aides are not always given a voice.

Stringent regulations are another barrier, she adds: “It is so hard to provide person-centered care in a nursing home. We can’t have residents walk in the kitchen and make a cup of tea.”

So great is the desire for more dignified and safer memory care, Gilmore-Bukovskyi believes, that untested ventures like Lily’s Promise will continue to create change through trial and error.

“One really clear message is that the development of new dementia care models, whether they’re environmental or philosophical, is a reflection of a really urgent need. Some of this demand will facilitate some discussion about how policymakers can incentivize this, and stop making it so hard,” she predicts. “It’s really an idea about how we respect and treat one another.”

Holik doesn’t need any scientific evidence for the change she perceives in her husband’s peace of mind after his move to the care home.

“He’s much more content,” she says. “He’s not agitated, and they don’t have him just lying down sleeping. And not only that, he’s much cleaner. Honestly, it’s just incredible. They cater to each individual. One of the caregivers talks to him about the presidential race.”

Now that Greelegs can no longer take part in the local Parkinson’s community, Holik feels fortunate to have found a place where he can still feel a sense of identity and security.

“It’s so different than any of the other facilities. It’s an awkward family, but families are all awkward,” she adds, laughing. “They sit together at the dining table and the caregivers are cooking in the kitchen. It’s like home, and it’s a nice home.”

Copyright © 2016 HeraldTribune.com — All rights reserved. Restricted use only.

We sat down with Heidi Godman of WSRQ Radio to discuss Lily’s Promise. Click